Born and raised in Moortown, Simon Glass, like much of Leeds’ Jewish community, can trace ancestral roots back to the Pale of Settlement in the western region of Imperial Russia. Working with the BBC on a new four-part series, A Very British History, capturing Britain’s immigrant communities on film, the young director travelled to Lithuania and Belarus to track down his family’s heritage and discover why they left for Leeds.

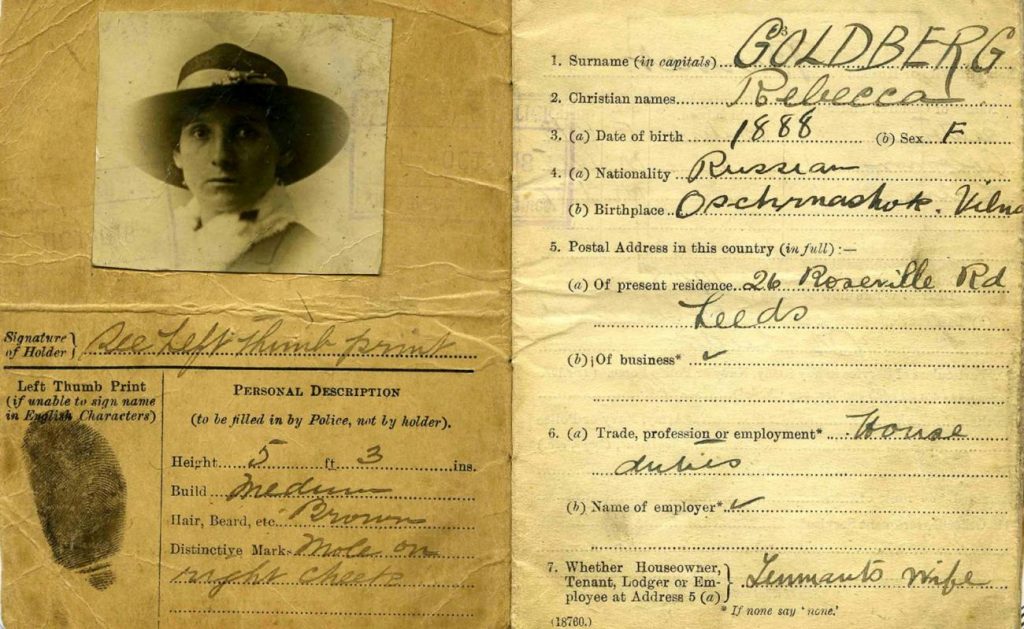

“By the time I was born, the last in my family from Russia, my great-grandmother Rebecca Miller died 10 years before. My cousin Rebecca Quest, named after her, had done a lot of work on our family’s genealogy, tracing my great-great-grandparents back to Lithuania, but it got to a point where she couldn’t trace it back any further. I’d always wanted to travel there and unravel our story and I thought this year [2018] I’m going back. Then, coincidently, the BBC got in touch and said they were making this series.”

Working with BBC researcher, Sue Wilkinson, Simon dug deeper into the archives and discovered his family wasn’t from Lithuania but in fact over the border in Belarus. “All we had was this name, Vashilishok, the village where she came from and the fact that her dad was one of four brothers. Just with this combination of details we were able to go back to Lithuania and track them across the border into Belarus. The Lithuanian state archives were remarkably intact. We were able to trace right to my great-great-great-great-grandfather – I never imagined we’d be able to trace it so far back.”

Like many living in the Pale of Settlement during the late 19th century, Simon’s family faced serious economic hardship and looked to the west for a brighter future. “My family had lived in this village for hundreds of years and it came to a point where they heard about the opportunities in England after the industrial revolution. Rebecca had an uncle, named Abraham, who was a very skilled tailor and had already left for Leeds along with her two older brothers evading conscription. One of the brothers continued to America, the other, was allegedly cast out of the Leeds community for stealing a bagel and moved up to Glasgow. Confronted with poor prospects, Rebecca also decided to take the journey west with the dream of making a better life for herself and her children.”

Not only does the film follow the story of those that left, but the fate of those who remained. “By the time the Nazis reached my great-grandmother’s village, the idea was just to kill as many Jews as they could. 2,000 people were murdered between 5th and 10th May 1942. There was one survivor. In the film, I meet 85-year-old Teresa. She was 10 years-old at the time and witnessed what happened that day during the massacre.

“Coming up from a community that isn’t made up of German survivors you don’t really associate the Holocaust as being a part of yourself. My mum told me Rebecca’s relatives used to send letters during the war but after the war ended, they stopped receiving them, so there was never really a connection made between our family in Leeds and those who died in the Holocaust. It was only when I went back through the archives and saw all these entries with the surnames Miller, I realised all these cousins of hers had been victims of this massacre. Only now do I realise how lucky I am my great grandparents came over when they did.”

Rebecca, like thousands of others, had escaped the unbeknown fate that had befallen those they left behind and in the early 1900s, travelled across the North Sea to the ports of Hull and Grimsby. Talking to Dr Nick Evans, a professor at Hull University, Simon charts the Jewish settlers’ progress across England, many of who were trying to get to America, but due to lack of money fell short. “At one point Newcastle, Middlesbrough and Sunderland all had significant Jewish communities but now they’ve virtually disappeared. Leeds has done a great job of keeping itself thriving. Even in the last 20 to 30 years as many, myself included, have begun to move away it really has proved itself a particularly resilient community.”

Simon puts this down to strong foundations in the cloth and manufacturing industry his ancestors laid down over a century ago. Rebecca built a life for herself in the Leylands just north of the city centre, where she witnessed her fellow settlers grow from a group of penniless immigrants to a thriving community commanding a burgeoning industry. “It was what most of the immigrants would have done at the time because they were cheap labour, but they also knew they could use it as a way for them to start growing their own small businesses. As a tailor you only need a machine, which costs very little to maintain, and some cloth. If you have a good supplier, the harder you work the more you can make and that’s why the industry boomed, especially for a Jewish community willing to put in the hours.”

Many of the biggest names in retail were born out of the Leylands. Montague Burton, founder of Burton Menswear came over from Lithuania. His factory on Hudson Street became the biggest clothing factory in the world. Similarly, Michael Marks, who had grown up in Belarus, arrived in the Leylands and set up a stall in Kirkgate Market, before meeting his partner, Thomas Spencer – the rest is history.

“You had these household names that boomed out of the entrepreneurialism of the Eastern European community. Burton capitalised on the Jewish community’s placement in the tailoring industry. Marks saw an opportunity in the market, selling good value products at a low price and he capitalised on that – ‘Don’t ask the price, it’s a penny’ was his old mantra!”

Simon emphasises that this work ethic was particular to a people who had seen untold famine and poverty, spurring them to make a success from humble roots. “The opportunity over here was far better than over there, so the last thing they wanted to do was go back, despite any untoward feeling they may have felt from the surrounding community. They thought if we keep our heads down and work hard six days a week, resting on the Sabbath, then we may not have a better life ourselves but at least our children will.”

However living standards in the Leylands were little better than they would have faced in the old country. “My grandfather, one of 13 was born in the Leylands and shared a room with his brothers as a kid. As soon as they could, they would have moved out of there. Chapeltown was the first place the community moved for bigger houses, then Moortown for bigger gardens, then Alwoodley for bigger streets, so you didn’t have to even talk to your neighbours anymore! In a way it’s just an ever-moving ghetto, and it’s the same in London and Manchester.”

Across the border from Vasilishok, the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius was one of the biggest ghettos in Europe. Dubbed ‘the Jerusalem of the north’ it was a target for Nazi extermination and was where many of Leeds’ Jews hailed from, giving its name to the New Central Vilna Shul which became Etz Chaim. From 1941 to 1944, 70,000 Jews, half the city’s population were murdered in the Ponary massacre. “I make a comparison in the film that the Vilnius ghetto was no bigger than the Leylands. Those in the Leylands probably would have felt threatened knowing what had gone on back home and what was about to happen in Germany, but took security in the fact they were surrounded by their own kind.”

Although Simon’s family escaped persecution in Russia, they were met with a number of challenges once they arrived. “The Aliens Act of 1905 was the first attempt by the British government to force some control over immigration. If you compare it to everything that’s going on with EU migration, you could look at it as the beginning as everything that’s happened since.

“Oswald Mosely, the leader of the British union of fascists and an acquaintance of Hitler, wasn’t taken too seriously on the world stage, (he was a bit of a 1930s Tommy Robinson) but he did a good job of rallying people against aliens: the code word for Jews. A couple of weeks before the infamous Battle of Cable Street in London where fascists marched against Jewish and Irish immigrants, Mosely tried to rally his army of Blackshirts on Holbeck Moor. In response, 1,000 Jews alongside English socialists and communists came together and chased him away. It shows that even back then Leeds was a place of tolerance and acceptance.

Although they weren’t welcomed with open arms, the Jews were keen to integrate into the British way of life. “It was through what these immigrants did in the early days, working hard and paying their way in society that they became accepted and paved the way for future generations to have a comfortable life. They really helped build Leeds and without them, the city may not have become as successful as it is today.”

The past year has seen Simon embark on a very personal journey, one made even more poignant when he arrived back from Vasilishok to news from Leeds. “The day I arrived back from the ancestral home of my great grandmother, I had a call from Mum telling me my great-uncle Jack had passed away. Jack Goldberg was 95, a tailor and a grocer and the youngest of Rebecca’s sons. Everything I had been working towards suddenly came into perspective – it was as if it was a final trip for him.”

Asked if the film has changed his perception of what it means to be Jewish and from Leeds, he replies, “Coming from Leeds and being Jewish you don’t think it’s that unique growing up because it’s the hand you’re dealt in life. When you venture out into London and the rest of the world you realise there’s a very small community here compared to others. At that point I took it on as a badge of honour. Being from Yorkshire is something you’re always proud of and being Jewish is something I took for granted. It’s not just a culture you can dip in and out of or a religion you can turn on and off, it’s an ethnicity.

“In a way, I feel part of being Jewish is about wandering and moving on. I remember when I made my first film, The Last Tribe, I interviewed a gentleman in his 90s, Sonny Jackson, and he said: ‘we’re a lot like Romani Gypsies – they’ve been trying to kill us for thousands of years but we’re still in business!’

“Jewish communities have a lot in common and now with Israel there is a place we can call our homeland. But for those who arrived in Leeds, there is only one homeland for them.”

on BBC1 in the Yorkshire/ Lincolnshire region in early December.