Celebrated Chapeltown animator and printmaker, Janis Goodman talks capturing the wild side of Leeds’ urban landscape.

“It’s a dark, mysterious art anticipating what people will like. The best thing you can do is please yourself in the hope that will please others.”

Janis has enjoyed what she describes as a “haphazard” career. In 1982, fresh from a degree in architecture at Cambridge University, Janis took up a year-long stint with Leeds Animation Workshop, the Harehills-based women’s collective producing animated films on social issues. She never went back to London, or architecture and “time just slid past…”

Janis resolved to come to Leeds on a whim, a casual decision given she’s been here nearly 40 years: “I thought it would be an interesting experience to live outside the south east, away from everyone I’d grown up with. A lot was changing, computer aided design was coming along and if you weren’t doing it, you’d get left behind. But really, there weren’t many jobs in architecture, so I thought it would be nice to do something different for a little while.”

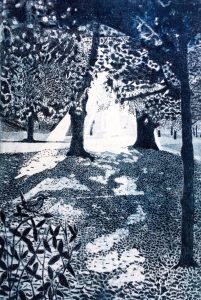

Now in her 60s, Janice still holds a fondness for her father’s architectural profession, much of her etching drawing inspiration from the built environment. Her prints comprise detailed monochrome etchings of natural and urban configurations, a dreamlike quality underpinning elements of realism, twisting the everyday to create something strange: “Perspectives offer a wider vision than you’d see without turning your head, so that gives it a slightly surreal feeling.”

A great deal of her work explores the tension between the manmade and natural environment – themes explored in etchings such as Land Marks depicting South Point, the derelict office block looming over the A61 flyover, and Cosmos in the Greenhouse stemming from a behind-the-scenes look at The Arium, the 90,000 sqm greenhouse in Whinmoor: “I quite like the idea of nature reclaiming the places we’ve abandoned. I’m always amazed how nature fights its way through, even within the containment of precise architecture.”

“I personally may have a dystopian vision, some part of me believing something cataclysmic will wipe out humanity and nature will strike back, but I like my work to reflect an optimism that I may not always feel. I couldn’t bear to make miserable art.”

Working from photographs and sketches, the nearby green spaces of Potternewton and Roundhay Parks and their avian residents form the basis of many of her works. For Janis, a sense of familiarity is important to faithfully representing her subject: “I have this conversation with a printmaker fascinated by hares. It’s a subjective thing to feel, but I believe you need a certain relationship with something before you can recreate it. I hardly ever see a hare – so I don’t feel qualified to draw them. But I’m always intrigued by the thought of Harehills being covered in hares once upon a time – ‘The Last Hare of Harehills’ could prove an interesting piece!”

Janis works from her home studio in Chapeltown, where etching paper can often be found soaking in the bathtub and wax melting atop the gas stove: “When it comes to covering the copper plate in melted wax, you’re meant to use a hotplate, but I can’t be bothered to acquire one when my cooker does perfectly well with an old baking tin on top!”

Working from home can be a lonely business; the bustle of the local print fairs where Janis sells her works often coming as a “shock to the system”. With exhibitions at Left Bank and Masham Gallery continuing to increase her profile, Janis has come to make a steady living from her art, yet she doesn’t believe the commercial element of her work bears undue influence on her process.

“Creating art with an audience in mind is a difficult thing to do. Things I think are wonderful are much less appreciated, and pieces I don’t think worked very well turn out popular – it’s a dark, mysterious art anticipating what people will like. The best thing you can do is please yourself in the hope that will please others.”

“I spent 15 years with printmaking as a developing side line – even early on, people wanted to buy them, which was astonishing to me. About eight years ago, funding in animation dried up and I was made redundant, not to mention recovering from a major operation after falling seriously ill, which always puts a different slant on things. But I still sold a few prints and since then, I’ve managed to keep my head above water.”

Janis has always drawn, but it was only when she took up an evening class at Leeds College of Art, she discovered the medium she would devote her artistic life to: “I love the subtlety of etching – it’s a very drawing-based process, only you’re sitting there with an etching needle rather than a pencil.

“In my animation work, I spent a lifetime drawing buildings, fields and mountains as backgrounds for scenes, and somehow that’s what my etching contains. Plus, there’s a whole lot of serendipity – interesting things that can go wrong, or occasionally right.”

“I like the fact you don’t just draw something, and it goes. You end up with a copper plate. That’s your original and it lives on when you print an edition. Unlike giclée prints, which are just inkjet reproductions with a grandiose French name, there’s a physical limit to how many multiples you can make, roughly 80, as the copper wears down, so they are truly limited editions.”

Janis believes there is something to be said for this physical process, in an era where computer aided design is becoming increasingly dominant: “There’s a depth to it. You can feel the indentation on the paper where the plate has been through the heavy press. None are quite the same, as each have been individually inked up and wiped. They bear the physical marks of a person printing them, which I think has real value.”

Janisgoodman.co.uk